I had been married to Alan Amos, my husband, for 34 years before I first went inside the church where he was priest-in-charge when we got married. This wasn’t for any complicated theological or ecclesiastical reasons, but rather because at the time we were married in January 1978, the church, All Saints Anglican Church in Beirut, had been sealed up to try and keep it safe during the Lebanese civil war.

The Anglican community in Lebanon goes back at least to the 19th century, and included merchants and traders, missionaries and educationalists. Over the years it grew to include foreign spouses of Lebanese, as well of course more transient members such as diplomats. It became – and certainly is today – international in scope – with many nations represented among the community. The common thread is the worship which takes place in the English language and reflects Anglican traditions and liturgy.

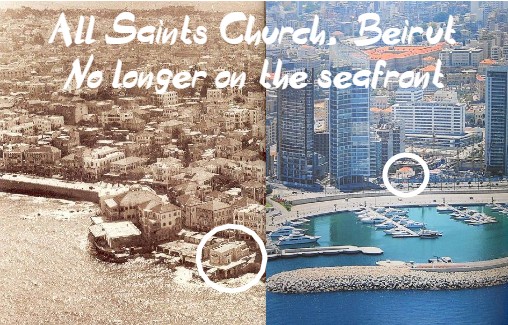

To begin with the community worshipped in borrowed buildings, but by 1912 they wanted to build their own church. A delightful site on the sea front in the area of Ain Mreisse was donated by the Joly family and work began, although due to the First World War the church wasn’t completed until 1929. Ownership of the church was vested in the Jerusalem and East Mission, the precursor of JMECA, and it is still owned by the J and EM Trust today.

In some ways the story of the church is a microcosm of the story of Lebanon. Initially there wasn’t an Arabic speaking Anglican community in the country. In the 19th century ‘dividing up’ of the Middle East between various western churches, Lebanon and Syria were allotted to the Presbyterians, just as Palestine and Jordan became Anglican missionary territory. The events of 1948 changed the demographic profile of Lebanon, of course, and among the Palestinians who came to the country around that time there were a group of Palestinian Anglicans who began Arabic services at All Saints. Over the years this community of Arabic speaking Anglicans from Palestine grew and flourished – indeed in the years immediately before 1975 they probably constituted the most numerous Anglican parish in the diocese, though now sadly, like many Christian communities in Lebanon, they are much diminished in size.

...the congregation grew to understand that the primary meaning of ‘church’ is as a community of people rather than a building...

Those years up to the civil war were a very positive period for the church. An attractive small building it was much loved by the people from many nations who worshipped there. Its location right on the sea-front gave it a certain cache – I remember hearing tales of one of my predecessors as a chaplain’s wife who would sometimes attend Sunday worship clad in her towelling robe, ready to discard this at the end of worship in order to dive immediately into the waters!

But its location at that strategic point also meant that when the civil war arrived in 1975 the immediate area of the church became the stomping ground for opposing militia. It became dangerous, then impossible for the congregation to get there, and the church itself was broken into and badly damaged time and time again.

...a new and very dangerous militia group who were controlling the immediate area, and who alternated between lining them up, threatening to shoot them, and offering them cups of Arabic coffee.

It was in summer 1975 that Alan, my future husband, was invited to become the chaplain of All Saints. He had originally come to Lebanon a couple of years earlier to lecture in the Orthodox seminaries. Taking on responsibility for an English speaking Anglican congregation had not been his initial plan in coming to the country, but given the fact that by the middle of 1975 the church was in need of a chaplain and the outbreak of the civil war had meant it would be difficult for a new person to arrive from overseas, he felt it right to accept the task when he was asked to undertake it. Indeed for a year or so from 1976 to 1977 Alan was also responsible for worship for the Arabic speaking congregation between the departure of Samir Kafity and the arrival some time later of Rafiq Farah, who then took over the responsibility for the Palestinian Anglican community.

Alan would say that his closest call and probably most dangerous moment during all his years in Lebanon was the day in 1976, when, alerted by a friend who was a Reuters journalist, they went down to the church together to rescue what turned out to be the Arabic hymnbooks which had been strewn outside. In the process they encountered a new and very dangerous militia group (an offshoot of the Mourabitoun) who were controlling the immediate area, and who alternated between lining them up, threatening to shoot them, and offering them cups of Arabic coffee.

By early 1977 it became clear that it was unrealistic to keep the church open. The last service held in the church for about 12 years took place on Ash Wednesday 1977 – there was plenty of dust and ashes around. The church was sealed up as securely as it was possible to do and artefacts like the stained glass windows were removed for safe storage. Both the English speaking and Arabic speaking Anglican communities began to worship elsewhere in the city in borrowed buildings. The English speaking community eventually found a temporary but very welcoming home in the German church, which because it was in the compound of the West German Embassy was comparatively secure. We moved in there shortly after I arrived in Beirut in January 1978 when I married Alan. There was of course a certain frisson to celebrating Battle of Britain Sunday in that particular location! But we could not have been better treated. Those years of exile from the building of All Saints were also an important learning experience for the church. Quite a few – though perhaps not all – of the congregation grew to understand that the primary meaning of ‘church’ is as a community of people rather than a building, however beloved.

The building of All Saints survived. It was sound in structure though badly damaged by vandalism and worse. It nearly disappeared in the 1990s when the relentless march of Solidere (the official post civil war redevelopment company) through Beirut almost led to it being levelled, but it was saved due to the initiative of Rev George Haddad who physically stopped Solidere’s workmen in their tracks. It was then very tastefully and joyfully restored, reopened and rededicated and both English and Arabic speaking congregations consider it their home once again. Some years later a bell tower was added, and eventually the undercroft was developed as space for a church hall. It is an attractive and very functional small church building, surrounded now by apartment blocks and hotels. It is no longer on the seafront however. The redevelopment of the city centre after the civil war led to earth and rubble being piled onto the shore – so All Saints is now about 100 metres from the sea. No more diving directly from the courtyard of the church into the waters of St George’s Bay!

Alan and I were privileged to be invited back to All Saints in November 2012 to celebrate the centenary of the laying of the original foundation stone. Archbishop Suheil presided, and we are grateful to the then chaplain Rev Nabil Shehadi for ensuring Alan was invited to be there.

It has not been particularly easy for either the English or the Arabic speaking congregations in recent years, as they have both of course been affected by the ongoing difficulties of life in Lebanon. We admire the leaders of both groups for their perseverance and determination to continue Anglican witness in the city.

The explosion of 4 August was a salutary reminder that Lebanon is still a land of considerable injustice, corruption and violence, which sits uneasily with the stunning beauty of much of its countryside and the multifarious talents and joie de vivre of its people. By a curious irony the fact that All Saints was surrounded by ‘mammon’ – those high rise hotels and apartment blocks – seems to have protected in to a considerable extent in this latest disaster. Though it is only located about 1 km from the epicentre of the blast the main damage to the building has been the shattering of glass, largely in the downstairs church hall.

While he was chaplain of the All Saints Anglican community in Lebanon (1975-82), initially based at ‘All Saints’ and then in other borrowed buildings, Alan wrote the following prayer, which was regularly used in worship. Please use it to pray for Lebanon today.

God bless Lebanon,

Guard her children,

Guide her leaders,

Give her peace;

May Lebanon become once again a place of unity in diversity,

Where all may learn to honour one another,

And humankind as your creation.

In the name of Christ we pray. Amen.

Clare Amos

Director of JEMT and JMECA

Published 11th Aug 2020